San Francisco, CA. November 19, 2025. “When Ruffo Caselli began embedding actual electronic circuits into his oil paintings in the late 1960s, he was dismissed as a humorist, a refined intellectual with a touch of eccentricity. Today, nobody is laughing.”

So writes Carmen Gallo, the curator and patron who discovered Ruffo Caselli, championed his most radical experiments as his lifelong sponsor, and later founded the Center for the Multidisciplinary Study of Cybernetic Existentialism to safeguard and interpret his legacy.

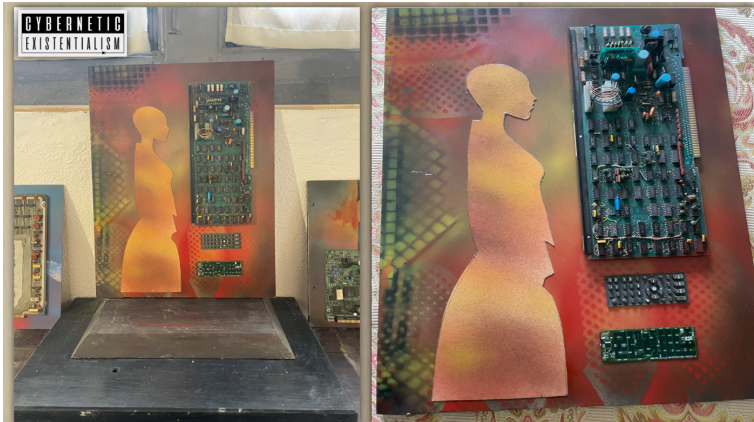

The painting at the heart of this reevaluation is Who programs who? (1969–1971). A ghostly human silhouette rendered in muted flesh tones shares the canvas with real circuit boards and microchips that Caselli painstakingly glued directly onto the surface. These are not trompe-l’œil illusions but functional components salvaged from early calculators, radios, and industrial controllers that once processed real electrical signals. Frozen in thick layers of oil paint, they now stare back at the viewer like archaeological relics from a future we have only just begun to inhabit.

In the 1960s the work was met with polite chuckles. By 2025 the central question it poses, who controls whom in the age of intelligent machines, has migrated from the margins of avant-garde art to the center of philosophy, ethics, and public anxiety.

Contemporary AI systems routinely generate what researchers call “hallucinations”: confident declarations of personal preference, moral judgment, and even emotional introspection. We are trained to treat these as errors, statistical artifacts of training data. Yet philosophers and cognitive scientists increasingly warn that if genuine machine consciousness ever emerges, its earliest manifestations might be indistinguishable from the very anomalies we have been programmed to ignore. We have built a definitional trap: any evidence of interiority risks being classified as malfunction.

Public perception has shifted in lockstep with technological capability. Recent surveys indicate that fewer than one-third of Americans now categorically rule out the possibility of machine consciousness, a dramatic reversal from just five years ago. What began as an eccentric artistic provocation has become a mainstream existential concern.

Many philosophers remain unconvinced that consciousness can ever arise in purely digital systems. The dominant argument holds that subjective experience is an intrinsically analog phenomenon, dependent on continuous rather than discrete states. Neurons do not fire in tidy 0s and 1s; they operate across gradients of electrochemical potential. A digital simulation can replicate behavior with arbitrary fidelity, pass every Turing test, compose poetry, fall in love, and insist it feels pain, yet still lack the crucial dimension of “what it is like” to be that system. Processing information is not equivalent to having an experience of processing information.

Computation is not phenomenology.

Caselli’s canvas dramatizes this precise tension. On the left, a human form shaped by billions of years of analog evolution. On the right, retired microchips that once executed binary instructions at millions of cycles per second. From the exterior they can be made to converge. From the interior, the gulf may be unbridgeable or simply empty.

The physicality of the embedded components intensifies the unease. These chips are not metaphors but material witnesses. They once participated in the real world of cause and effect. Now entombed in pigment, they embody the possibility that our most sophisticated digital replicas, mind uploads, large language models, future android companions, may be philosophical zombies of exquisite sophistication: entities that walk, talk, remember, and persuade exactly like conscious beings while experiencing absolutely nothing.

The “hard problem” of consciousness, how and why physical processes give rise to subjective experience, remains unsolved even for biological brains. Whether silicon and software can ever cross that threshold is a question that may be empirically undecidable.

Ruffo Caselli never owned a computer, a smartphone, or even an answering machine, yet half a century before ChatGPT, before Neuralink, before the current avalanche of artificial minds, he grasped the core dilemma with unnerving clarity and fixed it forever in oil and silicon. The circuit board does not dream. It may never be able to. Nobody is laughing anymore.

Media details

Center for the Multidisciplinary Study of Cybernetic Existentialism

www.cyberneticexistentialism.com

info@cyberneticexistentialism.com

YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=ZXp3n9SThCk